Technology That Does What People Want – Using (Rather Than Being Used By) Tools

Seventy years downstream from the first computers is enough time to take stock. Already, patterns emerge.

Even though today’s tech marketers ask us to accept a future that does “what technology wants,” in practice, the opposite appears to be true.

As explained in another post, The Next Thing After String, the march to the computer began with twine, weaving and the punch-card programing of the Jacquard loom. Along the way, people didn’t simply do “what twine wanted” and managed to lead normal lives after each of twines offspring. In prior episodes, the progeny of string caused some good and some damage. Bowstrings fed the family but also killed people. Industrial weaving made clothing affordable, but took a toll on garment workers. Over time, cultures made the adjustment to each new thing.

The same goes for today. Despite tech faddist dreams of mechanical humankind, new tech tools are most likely, after a break-in period, to lead to a human-friendly future. People have an interest in learning how to use these tools to create healthy people and communities, both human and natural.

Using, rather than being used by, a new tool or technology means a period of trial and error. Cultures try out something new and over several generations the kinks get ironed out. Casualties and success stories inform parents and innovators alike.

The cultural shock of problematic nineteenth century industrial technology met bottom- up social responses. These responses continue today with mixed results. People no longer accept slavery or sweat shop working conditions.Dumping hazardous waste is no longer normal. Industrial age drugs, cigarettes and alcohol are no longer chic and ever-present. Wars don’t feature atomic and chemical weapons, or torture. Human-animal genetic hybrids are fro

up social responses. These responses continue today with mixed results. People no longer accept slavery or sweat shop working conditions.Dumping hazardous waste is no longer normal. Industrial age drugs, cigarettes and alcohol are no longer chic and ever-present. Wars don’t feature atomic and chemical weapons, or torture. Human-animal genetic hybrids are fro wned upon. Tech oligarchs are no longer the social darlings they were just a few years ago. The progressive ideal, doing “what technology wants” has marketing horsepower only until the damage sets in and

wned upon. Tech oligarchs are no longer the social darlings they were just a few years ago. The progressive ideal, doing “what technology wants” has marketing horsepower only until the damage sets in and![]() people step in to set limits. The same process of setting limits on the use of our new digital toolkit is happening.

people step in to set limits. The same process of setting limits on the use of our new digital toolkit is happening.

Each innovation leads to its own parade of casualties and positive outcomes that point its generation into healthier directions. That goes for computer-age tools. Robots never lived up to their billing. They did not replace people, but just led new kinds of work. Smartphones are increasingly being recognized as a mixed blessing. Addictive apps and games have produced a generation of brain-damaged users. The result has been a new set of limits, prohibitions, and cautionary tales. Computer hazards are following the pattern of inevitable bottom up correctives that were seen when high potency pharmaceuticals morphed into street drugs.

Taking a look at the benefits of housebroken computational tools is what The Computational Age series is about. Among these tools, already firmly embedded in our culture, are simulation, data analysis, smart devices and the ubiquitous Smartphone. Most people own a Smartphone. Everyone takes for granted the miracle of improved weather forecasts and car designs that computer modeling makes possible. Grads are emerging from computational majors available in every major university. They will find careers, make fortunes and change the world.

Experiment revealed the world of the very small and very large. Statistics revealed hidden order in aggregates of things. These resulted in improved ability to extract value and work from nature. An image of an orderly, mechanical, clockwork universe determined by fixed laws was the worldview that emerged, replacing the medieval understanding of the world as an organic whole. With the scientific revolution and industrial age, the scientist and expert became the go-to trend-setters. This is changing.

Experiment revealed the world of the very small and very large. Statistics revealed hidden order in aggregates of things. These resulted in improved ability to extract value and work from nature. An image of an orderly, mechanical, clockwork universe determined by fixed laws was the worldview that emerged, replacing the medieval understanding of the world as an organic whole. With the scientific revolution and industrial age, the scientist and expert became the go-to trend-setters. This is changing.

Simulation and data mapping are new tools of discovery that are doing for this generation what the experiment and statistics did for industrial age discovery, invention and culture. Simulation is often a cheap substitute for experiment. It offers an admittedly imperfect vision of the future. Data mapping can reveal hidden relationships and connections that traditional lab methods failed to reveal.

Simulation and data mapping are new tools of discovery that are doing for this generation what the experiment and statistics did for industrial age discovery, invention and culture. Simulation is often a cheap substitute for experiment. It offers an admittedly imperfect vision of the future. Data mapping can reveal hidden relationships and connections that traditional lab methods failed to reveal.

The new tools put the spotlight on the surprising self-organizing and self-repair capacity  of communities. Order is said to emerge from living communities. In jargon, these are known as complex systems, a fancy way of labeling a community. Simple actions, such as cell division or a series conversation can create bottom up order in our world. Bits of matter interacting create galaxies. Cells dividing created the kaleidoscope of life. Simple interactions between people create economies, language, nations and cultures.

of communities. Order is said to emerge from living communities. In jargon, these are known as complex systems, a fancy way of labeling a community. Simple actions, such as cell division or a series conversation can create bottom up order in our world. Bits of matter interacting create galaxies. Cells dividing created the kaleidoscope of life. Simple interactions between people create economies, language, nations and cultures.

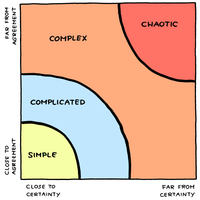

A world that includes the complex is what we see ever day. There are three types of things,

A world that includes the complex is what we see ever day. There are three types of things,

simple things that behave according to fixed rules, like a rock or a machine,

simple things that behave according to fixed rules, like a rock or a machine, chaotic things that obey no laws, like an explosion, a revolution or turbulence, and

chaotic things that obey no laws, like an explosion, a revolution or turbulence, and complex things, like communities, living things and galaxies, that are somewhat orderly.

complex things, like communities, living things and galaxies, that are somewhat orderly.

Communities make life and bottom-up order possible. Dynamic communities exist in what has been called the interesting in-between, that uncertain region occupied by the weather, stock markets, cocktail parties, brains, ant colonies, political bodies, humans, flowers, kittens, galactic clusters and cells.

Understanding that the dynamic and productive part of the world exists in that interesting in-between is a revolution. The result is a change in our worldview. The mechanical worldview of the age of laboratory science used to frame our thinking. It’s been demoted to the cul-de-sac occupied by mechanical inventions. In this emerging view, people will, in the long run, never simply do “what technology wants.”

An understanding of the world as made up of a mixture of chaos, stability and islands of complex life, goes a long way toward reviving the medieval understanding of the world as mysterious semi-order. Order and chaos exist companionably side-by-side, not in a New Age vision of the connectedness of all things, but in a way that allows people to exist companionably with the world. Institutions may make fewer of the dumb mistakes that often led to dead-ends and disasters. Benefits already seen include the rise of practical efforts at ecological restoration (rewilding and untaming), a new look at the utility of servant leadership as a model for business management, and models for personal development, parenting and education that leverage an appreciation of the importance of social networks and the architecture of the brain.

In 2000, Stephen Hawking identified the twenty-first century as the century of  complexity. The magazine, Scientific American, and author Michael Crichton, urged readers interested in careers and in creating a more livable world, to “embrace complexity.” That’s another way of suggesting that the new tools offer new understanding of the world as “complex,” but also that they hold great promise for careers and for healing of a damaged world.

complexity. The magazine, Scientific American, and author Michael Crichton, urged readers interested in careers and in creating a more livable world, to “embrace complexity.” That’s another way of suggesting that the new tools offer new understanding of the world as “complex,” but also that they hold great promise for careers and for healing of a damaged world.

Three or four generations downstream from the first electronic computer, it’s no longer necessary to speculate about the direction of computational culture. Science fiction hopes and fears are useful, but so is a sober assessment of career paths and opportunities for restoring the health of damaged natural and human communities.

Pointing out the signposts to a better future seems like a reasonable alternative to the  pessimistic predictions of a robotic future that tech marketers would like people to imagine. At least, it’s worth taking a hard look at what’s already happening, thinking about likely outcomes, chatting it up and, ultimately, enjoying the ride. After all, this is just another beak-in period. People are good at negotiating these. No big deal.

pessimistic predictions of a robotic future that tech marketers would like people to imagine. At least, it’s worth taking a hard look at what’s already happening, thinking about likely outcomes, chatting it up and, ultimately, enjoying the ride. After all, this is just another beak-in period. People are good at negotiating these. No big deal.